Space Traveler Terminology Quiz

Cosmonaut is a term used by Russia and the former Soviet Union to describe their space travelers. The word literally means “universal sailor” and was coined in the late 1950s to give the Soviet space program its own identity, separate from the American “astronaut”.

Quick Takeaways

- The official Russian name for a space traveler is “cosmonaut”.

- It was introduced in 1957 by the Soviet space agency to emphasize a global, humanistic vision of space.

- “Cosmonaut” differs from “astronaut” (U.S.) and “taikonaut” (China) in etymology, agency, and cultural context.

- Modern Russia still uses the term under Roscosmos, even for missions to the International Space Station.

- Key milestones - Sputnik, Vostok 1, Soyuz - cemented the cosmonaut legacy worldwide.

Why the Soviet Union Needed a New Word

When the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, shot into orbit in 1957, the world’s eyes turned to the USSR. American media immediately called the people behind it “astronauts”, a term derived from the Greek astron (star) and nautes (sailor). Soviet officials felt this ignored their broader philosophical aim: humanity as a whole, not just a few nations, sailing into the cosmos.

Enter Vladimir Chelomei and Sergei Korolev, the chief engineers who pushed for “cosmonaut”. The word comes from the Russian kosmos (universe) and the Greek suffix -naut. It translates to “universal sailor”, reflecting a vision of space as a shared frontier.

The First Cosmonauts and Their Missions

The title was first applied to the crew of Vostok 1 on April 12, 1961. Yuri Gagarin became the world’s first human to orbit Earth, and the Soviet press heralded him as the inaugural cosmonaut. His call sign, “Kedr” (Cedar), was used alongside the official title, reinforcing the new terminology.

Following Gagarin, the Soviet Union launched a series of historic missions:

- Vostok 2 - Valentina Tereshkova, first woman in space, 1963.

- Voskhod 2 - Alexei Leonov’s historic first spacewalk, 1965.

- Soyuz series - Introduced in 1967, the Soyuz spacecraft became the workhorse for decades, ferrying cosmonauts to low‑Earth orbit and later to the International Space Station.

Throughout these missions, the term “cosmonaut” was stamped on mission patches, press releases, and training manuals, solidifying its place in both Soviet propaganda and global space history.

How the Word Evolved After the USSR

When the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, the Russian space agency rebranded as Roscosmos. Yet the term “cosmonaut” survived unchanged. Modern Russian space flyers still receive the title, whether they launch aboard a Soyuz from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan or board a SpaceX Crew Dragon for an ISS stay.

Roscosmos even extends the title to civilian scientists and international partners who train in the Russian program. The concept remains tied to the original idea of a “universal sailor” - a person representing humanity’s collective reach into space.

Cosmonaut vs Astronaut vs Taikonaut

Three major space‑faring nations have their own label for space travelers:

| Term | Origin Language | Agency | First Use | Notable Firsts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmonaut | Russian (from Greek) | Roscosmos (formerly Soviet Space Program) | 1957 (officially 1961 with Gagarin) | Yuri Gagarin - first human in orbit |

| Astronaut | English (Greek roots) | NASA | 1958 (project Mercury) | Alan Shepard - first American in space |

| Taikonaut | Mandarin (tàikōng yǔnɡ) | CNSA | 2003 (Shenzhou 5) | Yang Liwei - first Chinese in space |

While the terms differ linguistically, the training pipelines share many similarities: high‑gravity centrifuges, T‑38 jets, and extensive scientific coursework. The distinct labels, however, reflect each nation’s cultural narrative about space.

Key Institutions Behind the Cosmonaut Program

Several organizations have been essential to the cosmonaut tradition:

- RKK Energia - the chief designer of Soviet‑era spacecraft, responsible for Vostok, Voskhod, and Soyuz.

- Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center (often called “Star City”) - the exclusive academy where hopeful cosmonauts endure months of physical, technical, and psychological preparation.

- Roscosmos State Corporation - today’s governing body that selects, funds, and integrates cosmonaut missions with international partners.

These entities not only provide the hardware but also shape the identity of the cosmonaut. For example, the “Cosmonaut Badge” forged from a silver alloy is presented at graduation, symbolizing the wearer’s entry into a historic lineage.

Cultural Footprint of the Cosmonaut

The word “cosmonaut” has seeped into literature, film, and everyday speech. Soviet movies like “The First Spaceship on Venus” used the term to evoke a sense of national pride. Western media, meanwhile, often uses “cosmonaut” to distinguish Russian flyers in stories about the International Space Station.

Even outside of aerospace, the term appears in product branding - from “Cosmonaut” coffee blends to “Cosmonaut” tech gadgets - capitalizing on the aura of exploration and durability.

Modern Day Cosmonauts and Future Prospects

Today’s cosmonauts are a blend of seasoned veterans and younger scientists. In 2024, Anna Kikina became the first Russian woman to join a NASA‑led Artemis training program, reflecting deeper cooperation between Roscosmos and its partners.

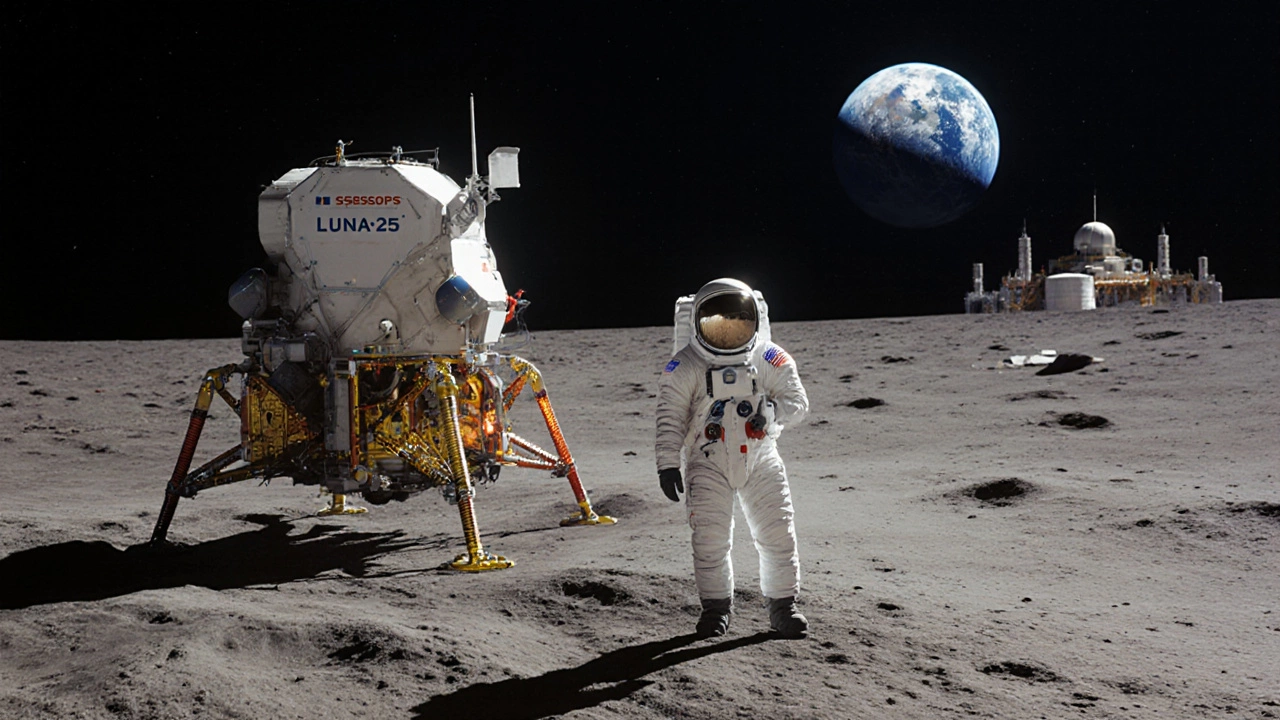

Looking ahead, Russia plans to launch a new generation of spacecraft under the “Luna‑25” program, aiming for lunar landings by the early 2030s. The cosmonaut title will likely accompany those missions, extending the universal sailor narrative from Earth orbit to the Moon and perhaps beyond.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did the Soviet Union ever use the word “astronaut”?

Officially, no. The Soviet press consistently used “cosmonaut”. However, informal English translations sometimes rendered it as “astronaut” for simplicity.

Is there a difference in training between cosmonauts and astronauts?

The core curriculum - spacecraft systems, EVA procedures, Russian or English language, and physical conditioning - is similar. Differences lie in the specific vehicle (Soyuz vs. Orion) and the national agency’s operating procedures.

Why is the term “cosmonaut” still popular today?

It honors a legacy that began with Gagarin’s historic flight and reflects Russia’s continued commitment to human spaceflight. The word also carries a unique cultural cachet that distinguishes Russian spacefarers in global media.

Can non‑Russian citizens become cosmonauts?

Yes. International partners who train at Star City and fly on Soyuz are officially designated as cosmonauts for the duration of the mission, though they often retain their home‑agency titles as well.

Will the term change if Russia adopts a new space agency name?

Unlikely. The term is deeply embedded in Russian culture and international discourse. Even if the agency rebrands, “cosmonaut” will probably stay as the descriptive label for Russian space travelers.